This week, we chatted with Jennie Lightweis-Goff about New Orleans, southern exceptionalism, urban plantations, and the lasting effects of Hurricane Katrina. We met with Jennie at her home in New Orleans to discuss why it’s important to imagine cities in the U.S. South, how urban areas of the U.S. South are as valid in their southern identity as rural areas, and what it means that New Orleans decided to take down its Confederate statues.

Benard de Marginy laid out the Marginy from land that had been his family's plantation just outside the old city limits of New Orleans. Today, we would consider this former plantation as squarely in the city.

Southern exceptionalism posits that the South is the exception to American exceptionalism while city exceptionalism imagines that cities are unlike their surrounding regions. New Orleans exceptionalism posits that the city is so different from the rest of the South (and country) that it can’t build stable connections to other places and people in the region. Jennie explains that frequently exceptionalism is a myth that we as people have to live by. It’s what makes one place feel like home more than any other. But it’s still a myth: “Every place is particular and no place is exceptional.”

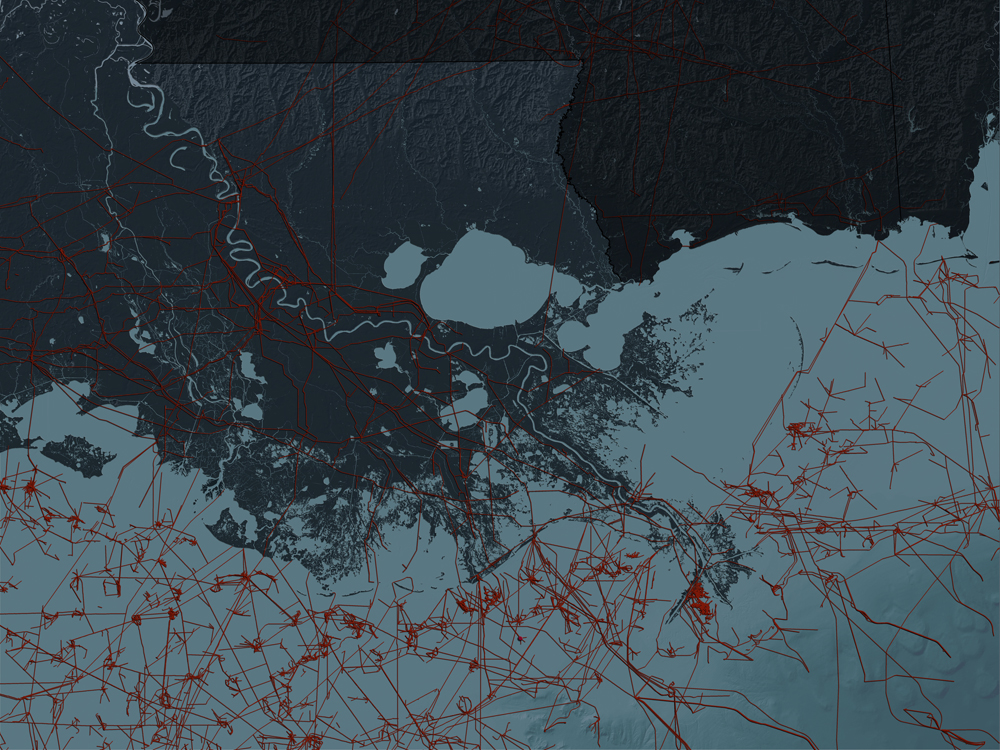

Looking down the arpent line, which follows the lines that use to divide French plantations in New Orleans.

Jennie has lived in New Orleans on and off since 2003. After Hurricane Katrina hit, the housing landscape changed: the city introduced more housing vouchers and did away with public housing. While tourists flock to the Ninth Ward, where water hit houses they way trucks hit houses, Jennie notes the relationship between the city and the supposed wilderness make it difficult to see the devastation today.

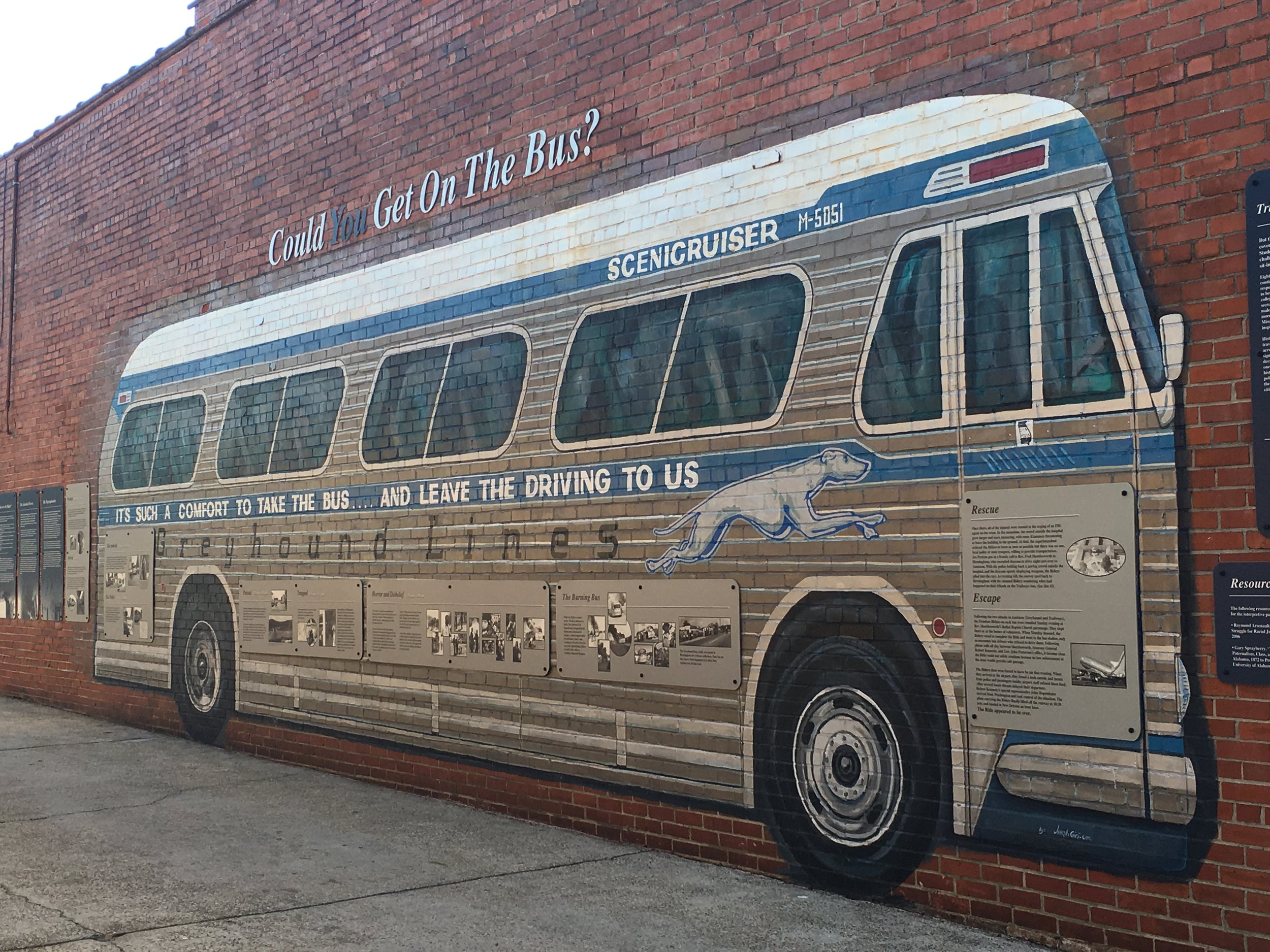

The conversation comes back to the things that make New Orleans just like every other southern city dealing with poverty, sprawl, climate change, and gentrification. Jennie recounts how public systems such as education and housing have become more privatized since Katrina, and as those institutions fail, the prison industrial complex swells. Mentally ill, uneducated, and homeless people end up in jail as a solution to social problems.

New Orleans in 2007

Though this interview was conducted several weeks ago, we end up coming full circle and discussing Confederate monuments. This past May, Mayor Mitch Landrieu pulled down symbols of the Confederacy. For Jennie, the statues of Robert E. Lee, P.G.T. Beauregard, and Stonewall Jackson produced a “solid south” where there never was one. The mayor posits the monuments stand as a large footprint of a small portion of the city’s history, one that creates a story that never really belonged to New Orleans. No one knows yet what will happen to the empty pedestals. In the mean time, they hold space for those who say their history was derided in the removal.

The empty Jefferson Davis pedestal in New Orleans. Photo by Bart Everson via Wikimedia Commons.

Jennie Lightweis-Goff is an instructor of American and southern literatures at the University of Mississippi. Her book, Blood at the Root: Lynching as American Cultural Nucleus, is available through SUNY Press.