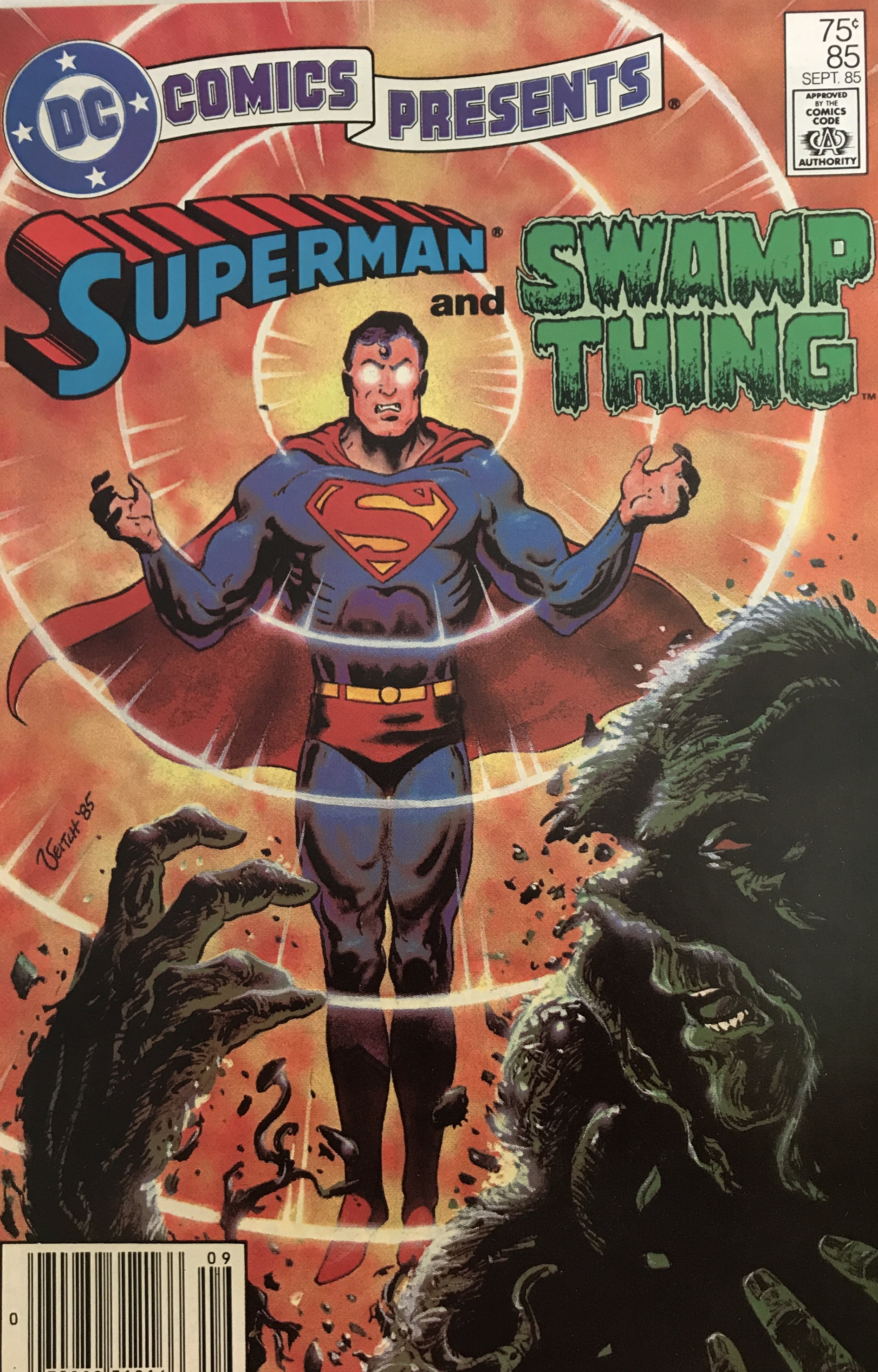

In an issue of Swamp Thing, Superman contracts a virus that will cause him to become violent. Instead of wreaking havoc in Metropolis, he heads south to Louisiana: a place where there are no superheroes. While Superman and his ilk may not make their homes in the south, the region has been richly explored in the comics medium: from early narrative comics such as Li’l Abner, Pogo, and Kudzu, to more recent serials and graphic novels such as The Walking Dead, Preacher, Bayou, and Swallow Me Whole. This week we visited Brannon Costello, English professor at LSU, to talk about southern comics. We discuss how comics explore the south’s relationship to the nation, grapple with the region’s history, and imagine its future.

Who could play Swamp Thing in a movie?

According to Brannon, cartooning about the south is as old as print culture, beginning perhaps with editorial cartoons about abolition and the Civil War. However, in the 1930s, Li’l Abner, set in the fictional Appalachian community of Dogpatch, USA, becomes one of the first narrative comics to explore southern themes. It is followed closely by the introduction of Snuffy Smith as the Appalachian cousin of Barney Google. These comics were a mass medium, with as many as sixty million readers during the height of their popularity. After WWII, Pogo, a comic strip featuring anthropomorphic animals set in the Okefenokee Swamp becomes widely popular, presenting readers with an idealized, pastoral swamp setting where national problems can be adjudicated in a light-hearted way. In the 1980s, as the south is becoming more urban and suburban, Doug Marlette creates Kudzu to explore these changes.

Lil' Abner from 1947

While the tropes of the superhero genre (as well as the location of major comic book producers) keep superheroes from venturing southward for most of the twentieth century, in the 1980s and 1990s, cartoonists and comics writers develop an interest in the south as a space that doesn’t fit into the genre. They explore the region as a "dark other." Southern “superheroes” greatly contrasts to the more urban superheroes: instead of the idealized physical specimens we see in Metropolis and Gotham, Swamp Thing is a shambling accretion of plants and mud who happens to think he’s human.

Superman comes to Lousiana

In a 1980s issue of Captain America, the titular hero quits his government job because he disagrees with the morality of potential missions. He’s replaced with a reactionary conservative from Georgia who becomes the new Captain America. The subsequent story line marks an attempt to think critically about what it would mean if Newt Gingrich was the new symbol of America, reflecting contemporary fears about the “southernification” of the U.S. When Captain America returns to his post.

We then discuss about some of Brannon’s favorite and least favorite southern comics. Brannon thinks The Walking Dead fails as a comic because it doesn’t exploit the possibilities of the medium in a particularly interesting way. He notes that although he’s still reading Southern Bastards and finds it visually interesting, it hasn’t yet fulfilled its promise to take a critical posture toward certain ideals about masculinity and the south. Instead, the series seems to be presenting the same tropes associated with the old south without a thoughtful critique.

Where will Southern Bastards go?

Some of Brannon’s favorite southern comics include Swamp Thing, especially from the period when Alan Moore and Steve Bissette; graphic novels March (written by John Lewis and Andrew Aydin), Swallow Me Whole, and Any Empire by Nate Powell; Preacher by Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon; Stuck Rubber Baby, a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age tale about coming out during the Civil Rights Movement; Bayou by Jeremy Love; Wet Moon by Sophie Campbell; and the adaptation of Octavia Butler’s Kindred by Damian Duffy and illustrated by John Jennings.

We would like to thank Brannon Costello for this interview. Brannon is an Associate Professor in the English Department at Louisiana State University. Together with Qiana J. Whitted, he edited a Comics and the U.S. South, published by the University Press of Mississippi in 2012. His book, Neon Visions: The Comics of Howard Chaykin will be available from Louisiana State University Press in October.

Places to help those affected by Hurricane Harvey: