In this episode, Gina visits Dr. Ben Frey, a citizen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and a professor in the American Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Ben talks about the current state of the Cherokee language and revitalization efforts in North Carolina. As Cherokee is the only surviving language in the Southern Iroquoian language family, it is remarkably unique. The Cherokee language is only about as similar to its nearest linguistic relative as English is to Russian. Ben discusses the importance of the language not only linguistically, but also as a tool to view his peoples’ knowledge about how to live in harmony with one another and the world.

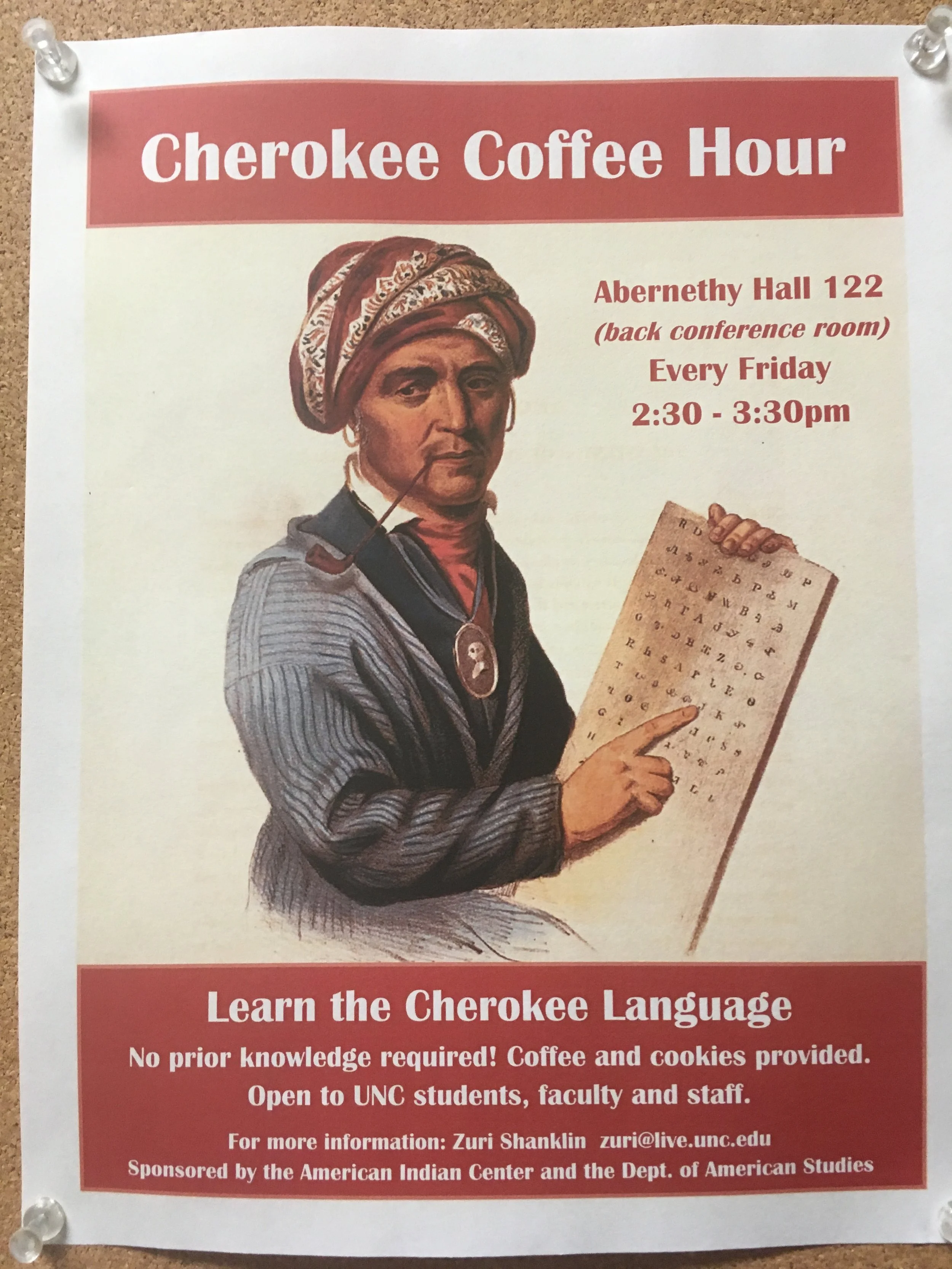

Ben Frey started a Cherokee language coffee hour at UNC.

The language is spoken by the three federally recognized nations of the Cherokee people: the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in present-day North Carolina, the Cherokee Nation in present-day Oklahoma, and the United Keetoowah Band also in present-day Oklahoma. Because of historical bias against Indigenous languages, the Cherokee language is endangered with approximately only 12,000 Cherokee speakers remaining across over 300,000 Cherokee citizens. Only 230 members of the Eastern Band speak the language. Many of the speakers are over the age of 65, and the language has not been passed on to younger generations. Although the language is publicly visible on street signs, store signs, and pottery, it is rarely spoken in public life.

Ben emphasizes the connection between the Cherokee language and the Cherokee people. He describes how his Cherokee elders posit that all things are endowed by the Creator with a particular vibration, and the Cherokee language is the vibration given to the Cherokee people as the sound with which they are supposed to vibrate. To him, that sound feels particularly southern, and it is tied to a specific place: the southern Appalachians, which are meant to echo with the sound of the Cherokee language.

Street Sign in Cherokee, NC | Photo by Billy Hathorn via Wikimedia Commons

Ben then turns to a discussion of current revitalization efforts. In both current-day Oklahoma and North Carolina, Cherokee people have created language immersion schools with the goal of exposing infants as young as six months old to the Cherokee language eight hours a day, five days a week. It began as a childcare program and developed into New Kituwah Academy in North Carolina. As the children have grown, the schools have added grades, teaching students all of their academic subjects in the Cherokee language. The immersion school in North Carolina recently graduated its first class of sixth graders, and the school in Oklahoma recently graduated its first class of high schoolers. Ben would like to encourage those high schoolers to come study with him at UNC Chapel Hill, offering “ᏙᏳᏛ ᎠᎭᏂ ᏤᏓᏍᏗ ᎠᏆᏚᎵ.”

Ben notes that although the language is endangered today, it wasn’t always that way. It was spoken regularly for over 14,000 years. As late as 1955 half of the community in Big Cove spoke the Cherokee language at home. He wonders how we might move beyond Anglo-centric bias to create a world where understanding Cherokee is meaningful and useful.

Ben urges both Cherokee people and non-Native speakers who would like to learn Cherokee to consider their motivations. Particularly because the language is endangered, studying it can be depressing or feel like an obligation, and for Indigenous people, it may bring up negative feelings about contemporary and historical traumas, but Ben encourages language learners to find their joy. And he suggests that non-Cherokee learners ask themselves what they can bring to the community as a language learner. He also urges those learning the language to set a small goal and develop a habit — to learn a few phrases and try to order a cup of coffee knowing that they will make mistakes, but understanding that they can laugh at these mistakes.

Ben Frey who will be translating Drake’s latest album into ᏣᎳᎩ.

We close this episode with a discussion of what Ben loves about the language and why he thinks the Cherokee language is important. He uses the phrase ᏙᎯᏧ to illustrate how the language creates and shapes relationships between people. Although this phrase might be translated into English as “how’s it going?,” the word ᏙᎯ means peace, slowness, and restfulness. The shift in emphasis in the Cherokee phrase marks a different kind of relationship between people.

Ben asserts that learning the Cherokee language is important because it gives us “a tool to view how our ancestors knew that they were supposed to live in the world.” He emphasizes that Indigenous cultures worldwide lasted for as long as they have and are still here because they were doing something right. That knowledge is encapsulated in Indigenous languages, and by caring for these languages, we care for this knowledge. In an era of climate change, hurricanes, deforestation, and violence against one another, Ben suggests that the whole world might benefit from learning Indigenous ways.

We would like to thank Ben for his time, and Mr. Ed Fields for all of his wonderful language work and his “Cherokee glasses.”

** During this episode, Ben discusses briefly the problematic term “Cherokee Princess,” noting that the term “Cherokee Princess” should set off alarm bells when we hear it because the Cherokee people do not have royal families. Furthermore, the etymology of the term might very well emerge from a time when Cherokee women were kidnapped and sold into sex slavery by people who “marketed” them as “Cherokee Princesses.” The term implies that one might have been forced into sex slavery, part of a history of violence against indigenous women which persists today, as indigenous women are disproportionately reported missing or murdered in both the United States and Canada.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Database: https://www.mmiwdatabase.com